Module 3: Prose

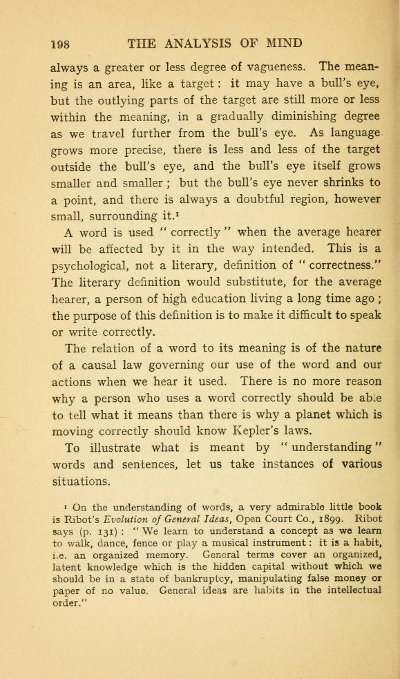

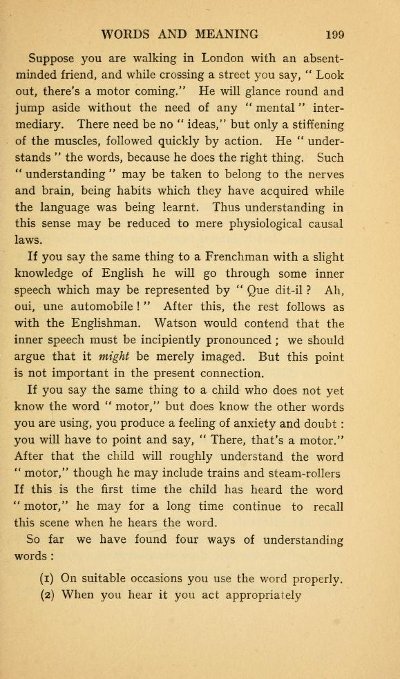

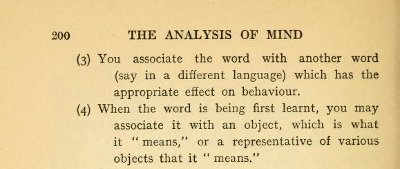

Have a look at the following extract of Bertrand Russell’s The Analysis of Mind (Russell 1924, 198–200):

Copy text to workspace

[198]always a greater or less degree of vagueness. The meaning is an area, like a target : it may have a bull's eye, but the outlying parts of the target are still more or less within the meaning, in a gradually diminishing degree as we travel further from the bull's eye. As language grows more precise, there is less and less of the target outside the bull's eye, and the bull's eye itself grows smaller and smaller; but the bull's eye never shrinks to a point, and there is always a doubtful region, however small, surrounding it.[1]

A word is used " correctly " when the average hearer will be affected by it in the way intended. This is a psychological, not a literary, of "correctness." The literary definition would substitute, for the average hearer, a person of high education living a long time ago; the purpose of this definition is to make it difficult to speak or write correctly.

The relation of a word to its meaning is of the nature of a causal law governing our use of the word and our actions when we hear it used. There is no more reason why a person who uses a word correctly should be able to tell what it means than there is why a planet which is moving correctly should know Kepler's laws.

To illustrate what is meant by "understanding" words and sentences, let us take instances of various situations.

[1] On the understanding of words, a very admirable little book is Ribot's Evolution of General Ideas, Open Court Co., 1899. Ribot says (p. 131) : "We learn to understand a concept as we learn to walk, dance, fence or play a musical instrument: it is a habit, i.e. an organized memory. General terms cover an organized, latent knowledge which is the hidden capital without which we should be in a state of bankruptcy, manipulating false money or paper of no value. General ideas are habits in the intellectual order."

[199] Suppose you are walking in London with an absent-minded friend, and while crossing a street you say, "Look out, there's a motor coming." He will glance round and jump aside without the need of any " mental " intermediary. There need be no "ideas," but only a stiffening of the muscles, followed quickly by action. He "understands " the words, because he does the right thing. Such "understanding " may be taken to belong to the nerves and brain, being habits which they have acquired while the language was being learnt. Thus understanding in this sense may be reduced to mere physiological causal laws.

If you say the same thing to a Frenchman with a slight knowledge of English he will go through some inner speech which may be represented by "Que dit-il ? Ah, oui, une automobile !" After this, the rest follows as with the Englishman. Watson would contend that the inner speech must be incipiently pronounced; we should argue that it might be merely imaged. But this point is not important in the present connection.

If you say the same thing to a child who does not yet know the word "motor," but does know the other words you are using, you produce a feeling of anxiety and doubt: you will have to point and say, "There, that's a motor." After that the child will roughly understand the word "motor," though he may include trains and steam-rollers If this is the first time the child has heard the word "motor," he may for a long time continue to recall this scene when he hears the word.

So far we have found four ways of understanding words:

(1) On suitable occasions you use the word properly.

(2) When you hear it you act appropriately

[200]

(3) You associate the word with another word (say in a different language) which has the appropriate effect on behaviour.

(4) When the word is being first learnt, you may associate it with an object, which is what it " means" or a representative of various objects that it "means."

Figure 1. Page facsimiles of The Analysis of Mind.

- Encode these pages’ main structures: paragraphs and page breaks, and encode them as a fragment of a book chapter (entitled “Words and Meaning”).

- Encode any lists (with a proper type).

- Encode the citation in the footnote. (note: on encoding footnotes, see Module 1: Common Structure, Elements, and Attributes, section 3.4.1)

- Encode quotations.

- Decide on the most suitable encoding of phrases with disclaimed responsibility, terms, or words mentioned.

Bibliography

- Russell, Bertrand. 1924. The Analysis of Mind. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., New York: The MacMillan Company. Facsimile edition made available by the Internet Archive at https://www.archive.org/details/analysisofmind00russ.