Module 4: Poetry

1. William Blake: Songs of Innocence and of Experience #

This example features a fragment of William Blake’s Songs of innocence and of experience, encoded and made available by the University of Virginia Library, for their Text Collection.

It forms a good example of how an anthology can be encoded. The work is considered as a single text (<text>) whose <body> contains both books. Both “Songs of Innocence” and “Songs of Experience” are encoded as <div1> numbered text divisions, with a @type attribute with value "book". Inside these books, all 45 poems are encoded as <div2 type="poem">. All poems have a title (<head>) and are subdivided into stanzas (<lg type="stanza">) and lines (<l>). Page breaks are recorded with <pb> elements, whose @n attribute contain the page number.

2. Robert Browning: “Porphyria’s Lover” #

The following example is the poem “Porphyria’s Lover” by Robert Browning. Although no formal line groups are discerned, it has a systematic rhyme scheme repeating every 5 lines. This is indicated in the @rhyme attribute of the outermost <lg> element. Some of the lines break up syntactic sentences; those have been marked with the value "yes" for an @enjamb attribute.

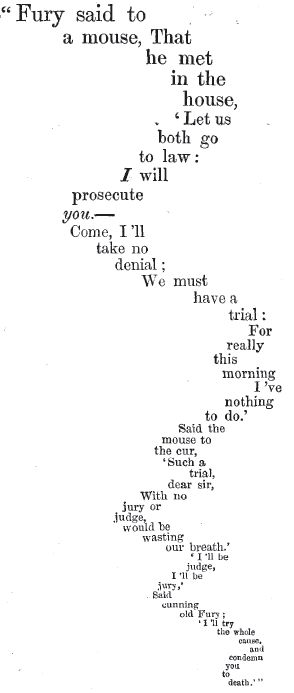

3. Lewis Carroll: “The Mouse’s Tale” #

The following example is an excerpt from Lewis Carroll’s “The Mouse’s Tale,” a poem appearing in the third chapter of Alice in Wonderland. It is a concrete poem in which the lines consist of only a couple of words, laid out in such a way that they visualise the mouse’s winding tail:

For the encoder, this specific visual layout challenges the TEI’s orientation to logical structures. In the example, the visual lines are encoded as logical lines (<l>); the visual particularities (font size, indentation) are formalised as values of a @rend attribute on each line. Of course, any value system is allowed for the @rend attribute; it’s up to the processing layer to decide how to interpret these values and format them on the screen / in print.

Reference

Since version 2.0, the TEI Guidelines have added a <sourceDoc> element, that allows for a topographic transcription of the content of primary manuscripts, organised in visual units <surface>, <zone>, and <line>. See chapter 11. Representation of Primary Sources of the TEI Guidelines.Alternatively, the lines could have been treated on a more logical level, spanning multiple physical lines. The line breaks then could have been encoded with <lb> elements, and specific visual characteristics as values for @rend attributes on <seg> elements. Since the white space is quite significant, the special-purpose TEI element <space> could have been used as well.

4. William Shakespeare: “Sonnet 17” #

The following example illustrates a very elaborate text encoding of a sonnet by William Shakespeare. As most sonnets, this poem is structurally analysed in three quatrains and one couplet. The lines themselves are further divided in metrical feet (<seg type="foot">) whose metrical analysis is provided in the @met of their containing <lg> element. For feet that metrically diverge from the metrical system, the actual metrical realisation is given in a <real> attribute. Where a foot runs over several syntactic phrases, the boundary between these phrases is marked with a <caesura> element. The rhyme scheme is encoded in the @rhyme attribute at the stanza level. In the example, the relevant <teiHeader> fragment is included for clarity’s sake.

5. Algernon Charles Swinburne: “Sestina” #

This example features a so-called “sestina,” a highly structured verse form consisting of 6 six-line stanzas followed by 1 three-line stanza. While the same set of six words conclude the lines of each stanza, in each stanza they occur in a different order. Since Swinburne in this example adheres to a strictly alternating rhyming scheme (if the internal rhyme of the tercet is not taken into account), the line ending patterns in this example vary from the traditional structural pattern for a sestina.

In this example, the rhyming scheme is indicated per stanza, using the @rhyme attribute on the stanza’s <lg> element. Rhyming words are marked with <rhyme> elements, with a @label attribute indicating their place in the rhyming scheme. In order to trace the line ending scheme, the ending words of the first stanza have been identified with an @xml:id attribute. Since they were already marked with a <rhyme> element, identification happens on this level. In the other stanzas, each line ending word is connected to its counterpart of the first stanza with a @corresp attribute. This is one of the global linking attributes, whose value formalises a correspondence relationship with another identified element (see the TEI Guidelines section 16.4 Correspondence and Alignment). Since the reference is to a local element (an identified element in the same document), its value takes the form of a shorthand local pointer by simply preceding the target’s @xml:id value with a hash sign #. Here too, the <rhyme> element provides a sufficient peg for pointing out this correspondence. Otherwise, if no other element would have been available, a <seg> element could be introduced for identifying or referring to a span of text.

Bibliography

- Blake, William. 1789. Songs of Innocence and of Experience. London: W Blake. Encoded and made available by the University of Virginia Library, Text Collection at https://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/BlaSong.html.

- Browning, Robert. 1842. Dramatic Lyrics. London: Moxon.

- Carroll, Lewis. 1865. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. New York: D. Appleton and co. p. 37.

- Islam, Mubina. 2004. “A Selection of Sonnets: electronic edition encoded in XML with a TEI DTD.” Unpublished Master’s Dissertation, London: University College London.

- Shakespeare, William. 1978. The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. Edited by Alexander, Peter. London: Collins.

- Swinburne, Algernon Charles. 1924. Swinburne’s Collected Poetical Works. London: William Heinemann. p. 330–31.